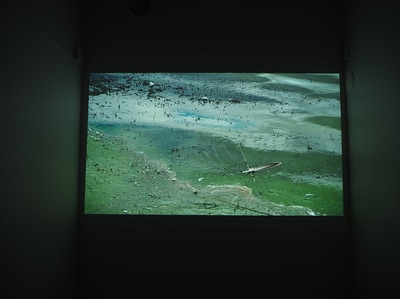

Waterlilies: an Ode to Lake Horowhenua

A study of toxic algal blooms in the manner of Monet

A Brief History of the Lake

Lake Horowhenua was once the centre of a rich wetland ecosystem surrounded by podocarp forest. It is Maori land, home of the Muaūpoko iwi.

In the 1820’s the lake was the scene of a fierce attack by Te Rauparaha and Ngati Toa on the Muaūpoko people. Two island pā, constructed on the lake as refuges for women and children were destroyed, their inhabitants taken hostage and subsequently massacred. The lake bed is littered with their bones, along with those of the many warriors from both sides killed in battle.

Since then, the trees have been felled, the wetland drained. Muaūpoko were granted the land in the Treaty of Waitangi settlement, but effectively lost control of the lake in the early 1900’s when legislation was drafted giving Pakeha settlers usage rights. Since then, it has become a popular venue for recreational boating, an activity which remains contentious to this day.

Between 1952 and 1987 treated sewage was discharged directly into the lake where it remains as a deep layer of sediment covering the lake bed.

Levin’s sewage treatment plant, about 500 metres from the lake edge, now discharges treated effluent to land on a nearby forestry block, although, on several occasions flooding has caused the plant to overflow, spilling more effluent into the lake.

Storm water overflow, along with run off from intensive dairying and market gardening have increased nitrate and phosphorus levels in the lake, contributing to the growth of invasive weed and toxic algal blooms.

The Lake Horowhenua accord was drawn up by the Horowhenua District Council in 2013 to introduce measures (riparian planting, stream fencing, management plans for nutrients, weed removal from the lake) to mitigate the degradation of the lake. These are voluntary measures with no time frame for implementation, nor legal consequence for non compliance.

In recent times, the dismal water quality of our lakes and rivers has finally become a hot topic, perhaps because it is now threatening our tourist industry and New Zealand’s precious clean, green image. For many town dwellers, this is a problem that is heard about rather than experienced, an ecological concern without emotional connection. With this exhibition I aim to confront the viewer with the actuality of the water and its adornments, using the aesthetic hook of abstract expressionism to capture the viewer’s attention.

I didn’t deliberately set out to base a body of work around Lake Horowhenua. Rather, it found me. I have no ancestral connections to the region. I made photographs as an outsider looking in, mesmerised by what I saw, the poignancy of its past and the continuing battles for its future.

I didn’t deliberately set out to base a body of work around Lake Horowhenua. Rather, it found me. I have no ancestral connections to the region. I made photographs as an outsider looking in, mesmerised by what I saw, the poignancy of its past and the continuing battles for its future.